RICHES TO RAGS: Thomas Houlette and the Anchor Mountain Mine

by Jeff Jacobsen

SYNOPSIS: In the summer of 2009 I started looking into my great grandfather's role in managing the Anchor Mountain Mine west of Galena. Because there was little family history to go on, I had to use all the resources I could find. From my exploration of Galena history, Black Hills mining history, and following my great grandfather's work history, I built a more detailed, but still not complete, understanding of both Anchor Mountain Mine and my great grandfather.

* * * * * * * * *

Custer Peak mine

Galena is a silver mining ghost town nestled in a quiet gulch about 10 miles from the more famous city of Deadwood, in the northern Black Hills of South Dakota. The town maintains their school house built in 1882 and retired in the 1940s, which is sometimes used by nearby grade schools on day trips to give kids a taste of what life was like in a one-room, one teacher school with no indoor plumbing. It may be a testament to the community that the school outlasted the 13 saloons and 3 churches that were flourishing during Galena's boomtown phases. Galena is named after the lead and silver ore found in the mines around the gulch, most of which were money losers.

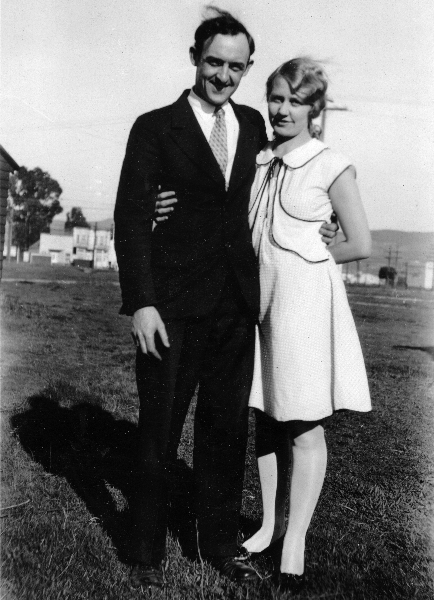

I grew up visiting my grandmother Lillian in Galena on weekends, or staying with her off and on during the summers. She lived alone in different cabins there over the years, and her sister Rosie lived in a home not far down the road that was a famous eating establishment for many years. I'd spend my time exploring in the spruce and pine covered hills, or tramping around with Lilly and Rosie as they dug through dumps from bygone days, hoping to add to their bottle collections. It was a time and place to breath in history, including my own family's. Both Lilly and Rosie had gone to school in Galena, and even my mother went to grade school there for one year. My grandfather Howard Houlette and great grandfather Thomas worked at the Anchor Mountain mine up Butcher Gulch about a mile and a half from town. Lillian had been the cook at the 22-bed boarding house there in the late 1920s, and that's how my grandparents met.

Howard and Lillian Houlette

For the last few years while working on a Political Science degree in Arizona, I've spent the summers in a tiny cabin on the north end of Galena. My siblings and I bought it from my mom and step father so we could keep it in the family. My grandparents had lived there while Howard was working at the mine, and later Lillian lived there for around 15 years on her own. We have a photo of my mom outside this cabin in the snow, age about 6, all bundled up and sitting with a friend on the bumper of the family car. So while it has historical significance to us, the cabin is a bit primitive. It has a well with a hand pump, an outhouse, a makeshift outdoor shower stall, and a wood stove for heat. It has no insulation in the walls, and I don't think it had attic insulation either until about 20 years ago. Even though my grandmother happily lived there all year round, for me it's a nice summer cabin. I'm not as tough as my grandmother.

Edith (right) and friend in Galena

Last May after graduating with a Bachelor's degree (President Obama was my commencement speaker), I was back in Galena, investigating the Anchor Mountain mine. I was enticed to dig into the mine's background more after my brother Eric found a prospectus written by great grandfather Thomas Houlette in about 1936. Thomas was seeking $30,000 to install some new equipment and restart the mill there. The U.S. economy was pretty shaky at that time, and his attempt failed. The mine was abandoned. The site was unpatented, meaning they were just there based on mineral rights. It's Forest Service land now. There's not much to see today other than the concrete foundations of buildings, a couple of crumbling ore cars, and the piles of waste rock hauled up from the 200 foot deep shaft, and the now water filled tunnel. There's also a strange circular concrete structure called an arrastra that was used by the first miners to work the claim.

I hiked up the rough road to Anchor Mountain and took photos of the remains, labeling each picture based on the map included in the prospectus. I could not find one tunnel and a cabin shown on the map, but everything else fit well.

Interestingly, the bull wheel was made with square nails, while everything else had round nails. A bull wheel is made of wood, about 5 feet in diameter, and is attached by a belt to the power source, usually a steam engine. The wheel had a shaft that turned the cams for the stamps and any other equipment needing power. The square nails indicated to me that they probably got the bull wheel and stamps from an older mill somewhere in the hills that had closed down. Round nails came into use around about 1910.

Anchor Mountain mine bullwheel

But now I began to wonder about this mine. Had it been successful at one time? How long had Thomas managed the mine? How did he wind up there? Was he any good at it? I had never heard anyone in my family talk about such things. My grandmother and others who might know were gone, and I didn't know how to find out the history of this place.

The Black Hills was full of mining claims. Since the gold fever struck after General Custer's expedition in 1874 found gold in the streams, there was a stampede into the hills, even though a treaty with the Sioux Indians forbade whites from entering the Black Hills. Nevertheless, by 1890 there were about 30,000 mining claims, about half of which had been prospected enough to prove their worth, or worthlessness most likely. Most of these were looking for gold, but there were also silver areas like Galena, Carbonate Camp off Spearfish Canyon, and other places.

My grandmother's book collection still resides in the cabin, on the brick and board bookshelf. Several of the books are of the mining history of the Black Hills, so I started my investigation there. I decided to simply read all the books from cover to cover and mark any places with family or mine interest. There wasn't much. Thomas is mentioned in Irma Klock's book "Yesterday's Gold Camps and Mines in the Northern Black Hills." She says "Houlette and Kenworthy started building a mill but along came the Depression... and the mine was closed." She also says the meals at the boarding house were very good, which is a nice compliment for my grandmother. Another book mixes the history of the Anchor mine, which was a different mine in the Ruby Gulch farther south, with Anchor Mountain. Thomas Walsh sold his stake in Anchor for $30,000 and went to Colorado to pay the half he owed to his partner. While snooping around mines in the Ouray area, he happened upon tailings with rich ore that had been missed by the previous owners. He purchased and reopened the Camp Bird mine and became a multi-millionaire, becoming famous for buying his daughter the Hope Diamond. Walsh's cabin in Galena, the size of a small garage, is still standing.

In the Ken Waterland book I found out that Thomas was vice president of another mine, the Custer Peak Copper Mining company, about 13 miles south of the Anchor Mountain. This mine ran from 1907 to about 1919, but there was no mention of what years Thomas was involved. And no mention of how successful this mine was either.

From the books it was clear that Galena had a mostly inglorious mining past. Most mines never amounted to anything. The famous and somewhat prosperous ones had troubles and they closed as well. And two of the most prosperous, the Sitting Bull and the next-door Richmond, wound up in a court battle that changed mining law for the entire country.

Back in the 1970s my brother and I took some church friends into the Sitting Bull mine. As with many of the mines in the area, the tunnel was still accessible. Most shafts have fortunately been plugged, but adventurous young people with little sense can still tour some of the tunnels brought about by great labor and lots of dynamite. The Sitting Bull mine has thousands of feet of tunneling that cross this way and that, and we had brought pieces of paper to leave along our trail so we could find our way out. We knew little of what to look for as far as the ore veins or what the rock could tell us, but we had fun exploring and seeing the equipment left behind and the wooden storage area covered with some strange white fungus. Long ago, clear in the farthest reaches of the tunneling my great uncle had written his name with "1933" under it.

Colonel Davey, who ran the Sitting Bull, had been following the ore back into the hill, when his tunnel wandered over the claim border onto the neighboring Richmond mine's property. This imaginary line going from the surface underground was sacrosanct in the mining business, but Davey claimed he was following the Apex, or the vein that started on his property, so he had a right to continue on wherever it took his miners. Davey had no experience mining until he came to Galena, so perhaps he could be forgiven for this legal faux pas. The Richmond owners cried foul, claiming there was no apex starting from Sitting Bull, but rather the whole hill had the same angled layer of ore and was thus not solely in control of Davey. Off to court they went.

In 1887, after 4 years, the courts decided for the Richmond. Davey appealed, but in 1889 he gave up and sold all his sizable holdings in Galena, including a mill and the Florence mine on the other side of the gulch from the Sitting Bull. Mining law had been changed, but at the expense of the little mining community of Galena. During the years of court battle the major mines in the gulch had been closed. 125 people just on the Sitting Bull side had been put out of work. Galena never recovered.

Since the mill had also been closed during this fight, it crimped the ability of the other smaller mines. Ore needs to be dug out, then processed to separate the gold or silver. If the milling couldn't be done locally, it was shipped to places like Omaha, Nebraska, hundreds of miles away, by rail. The freight charges cut deeply into any potential profit.

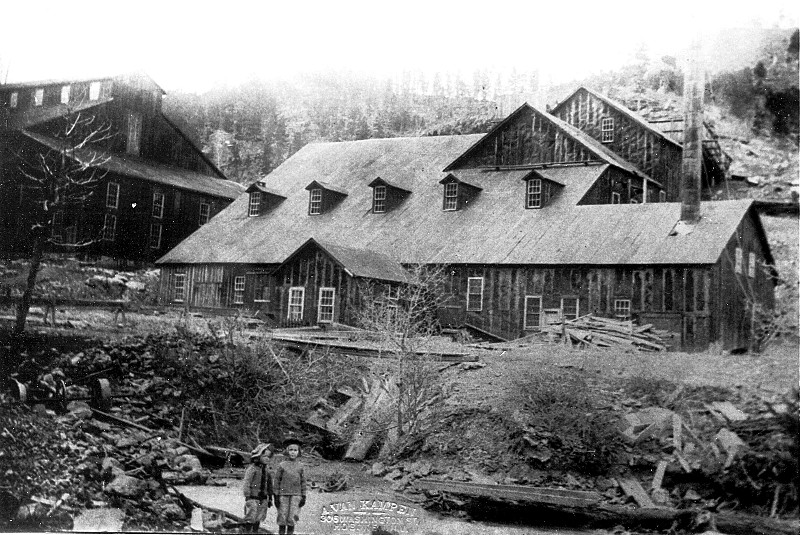

By 1897 Galena mining was bust. But then James Hardin came to town. Hardin was considered the best mining promoter in the Black Hills. In 1902 he built a huge mill at the far end of town, and a 3-mile narrow gauge rail track to haul ore from his mines in the Gilt Edge area farther south. This track runs behind our cabin. Things again seemed to be on the upswing, and this convinced the Burlington railroad to run a spur into town.

Florence Mill in lower Galena (Rosie and Lillie North in front)

But Hardin's ventures also failed. Another later mill, the Osterman, was mostly built around 1910, but it never opened for business.

That was about it for most mining in the area except for a few stragglers like Anchor Mountain. In the 1960's the Homestake Mining Company from Lead, which was running the largest gold mine in the U.S., decided to spend some time investigating the Double Rainbow Mine shaft below the Sitting Bull. Apparently they didn't find enough of interest, and that closed a few years later. But they did, unusually, haul away all their tailings. Brohm mining worked the tailings and old mines in the Gilt Edge area for several years, but then in the 1990's they had a disagreement with the state and filed bankruptcy, leaving behind a toxic mess that is now a Super Fund site.

My grandmother's books gave me a comprehensive look at the colorful history of mining in Galena, and added a mine to Thomas Houlette's resume. My cousin Jeraldine, who probably knows more Galena history than anyone alive, suggested I look in the Lawrence County courthouse in Deadwood for records of the mining claims and other documentation. The clerk of courts is in a nice addition to the old original courthouse. The old books are huge, perhaps weighing 20 pounds each, and are covered in burlap and leather. The old documents were written out by hand in sometimes stunningly beautiful calligraphy, so it is a pleasure just to look at and heft these time capsules of mining history. Someone has fortunately made an index of the mining claims, so it wasn't hard to find the books with Anchor Mountain information.

The first record for a claim at Anchor Mountain was from Robert Perli, in 1912. I knew Perli's name because of the old homestead they had in Lost Gulch about a mile north of Galena. Their log cabin, since burned down, had Italian newspapers covering the inside walls. All that is left of their place now is some of the log walls of their barn. In about 1915 Robert Bolger is listed as being a co-claimant to Anchor Mountain. Jeraldine had a photo titled "Bolger Mill" that had been on the Anchor Mountain site, but with no year on it. The mill appeared to be higher up the hill than where the ruins are now, but I can't be sure. In 1916 an article in the Deadwood paper stated that Bolger and Perli were getting "good results" from their arrastra, but with no specifics. When reading old articles and reports about Black Hills mines, the adjectives are often "good" or "promising" or some other positive word, but seldom are there specifics.

Anchor Mountain Mining Company first shows up in the county records in 1919 as the new owner after multiple swaps between Bolger, Perli, Bolger's wife, and a Pyrdith Hammond. Thomas doesn't appear until 1931, as president of the mining company. But I know he was there before that because my grandparents met at the mine around 1928. We have a photo of my grandfather at the mine with a few other men from that year. As always, my grandfather is smiling. I wish I could remember him better, but he died when I was 6.

Another source of information for me was, of course, the Internet. After reading my grandmother's books and pouring over the county records, this was my next step. I typed "Thomas Houlette" into google and got some hits in Google Books. How google chooses which books to scan, I have no idea. But some very obscure books that they chose helped open up history for me. A report of the 1906 legislature in New Jersey lists Thomas Houlette Company as doing business there. The 1907 Pennsylvania legislature revoked the licenses of hundreds of companies for nonpayment of state taxes. Included in that list of companies was Thomas Houlette Company. According to my grandmother and other family members, Thomas ran a successful construction company in Pittsburgh, specializing in high-rise buildings. They were rich enough that they had a live-in nurse for their 5 children. She gave each child a pet name. My grandfather was Bep. Mary Lynn, a granddaughter of Thomas', recently visited relatives near Pittsburgh. She sent me photos of some of the houses Thomas had built around 1890. They are still in fine shape and are happy homes to this day.

the Houlette home in Pennsylvania

An annual book called Mines Register listed all the producing mines in the country and what the situation was in each. I could see no justification why Google would choose such books out of all the books in the world to scan, yet here was some precise information about the mines Thomas ran. He was listed as vice president or president, depending on the mine and the year. Generally, the mines were listed as idle or being renovated. No actual production is shown. Whoever makes google's book scanning decisions, thank you.

At this point I knew that Thomas ran two mines in the Black Hills; the Custer Peak Mining Company, and Anchor Mountain. I knew the approximate years. It appears that they weren't very active mines from what scant information I could glean. Somehow, I was hoping for more than this. How much actual ore did they get from the mines? Were they profitable for their investors or a flop? Did Thomas bloat the potential of the mines to his investors? Why did he leave his successful business in Pittsburgh to chase after gold? What did he know about mining in the first place?

I called my mom and asked if she had the phone number of any other Houlette relatives who might know more about the mines. She gave me her cousin Forey's number. He in turn told me to call Jean, who was the daughter of my great Aunt Ethel. Even though she's 91, Jean was sharp and happy to talk to me. She told me Thomas first went to Jerome, Arizona to run a mine there. This was news to me. She gave me some other tidbits of information. When I asked if she might have any old photos from the mines or of the family back then, she said she thought they had thrown away most of the albums during her last few moves. This was bad, because my family hadn't kept or had many photos either. She said she'd ask her daughter to be sure.

Mary Lynn, Jean's daughter, called later and said she'd look into what she could find. Meanwhile, I called the South Dakota Historical Society in Pierre, South Dakota. Ken Stewart spoke to me. He had lived in the Black Hills and his father had even been state mining inspector for a time! He knew of some information they had of Anchor Mountain, so I said I'd make the half-day drive in about a week. Ken promised to have all the information he could find ready for me by then.

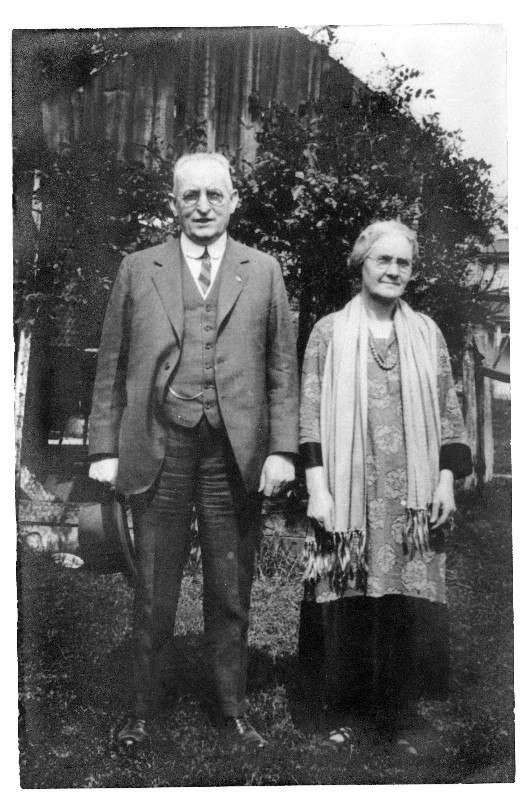

Mary Lynn emailed me to say she had kept some of their photo albums, and she had found some photos of Thomas. She started sending them, and I got my first look at my great grandfather and great grandmother. The photo of them together was taken in Harmony, PA. They were dressed formally. They appeared to not be very affectionate toward each other. Mary Lynn sent more photos, and filled me in on a bit more information.

Thomas Houlette and his wife

Something I had never heard, but apparently everybody else knew, was that Thomas had run off with another woman when he was in the Black Hills. There were varying accounts of when this happened, but it upset my grandfather enough that he had ripped up all the family photos of Thomas. Thus the scarcity on my side of the family. Mary Lynn also said that Thomas had first gone to Jerome Arizona for a mining venture there. While I had never heard of this before, when I told my sister and brother about it, they said "oh yeah, we knew that." Apparently, there was more information right in my family yet to be drawn out.

In Pierre I made copies of a report on the Anchor Mountain Mine area done in 1989. The Brohm company was treating the tailings in the Gilt Edge at the time, not far from Anchor Mountain. They wanted to use the Anchor Mountain site, which is Forest Service property, to dump some of their tailings. That doesn't say much for the mining value they saw in the property, if they wanted to bury it. The State of South Dakota ordered them to conduct research on the area first to see if there was any historical significance. This report concluded that there was, since the only surviving arrastra in the Black Hills was there, and because of other remains still present. Interestingly as well, the researchers had talked to Lillian my grandmother, and she had provided some old photos from the mine. These were photos I had never seen before of construction of the mill there. There was also a photo of some of the workers, including my grandfather. The report said that the photos would be donated to the South Dakota School of Mines.

When I got back from Pierre I went to the School of Mines library, but they had no record of such photos. I called the company that produced the report. The owner told me he'd look for the photos or what happened to them, but he never called back. My assumption is that Brohm has the originals, and Brohm went bankrupt. So all we have is photocopies of the photos out of the report.

About this time, in my google books search, I had run across Thomas Houlette's name as vice president of the Jungle Mine in the Black Hills. This was somehow associated with the Custer Peak Mine. Suddenly, Thomas was a serial mining company manager! And at first I only knew of the Anchor Mountain Mine connection. Now it turned out he was an interstate, multi-ore miner. The Jungle Mine, according to Waterman, had been contracted to provide copper ore for the Osterman mill. But the mill never opened.